What defines art?

An artwork doesn’t become art just because auction houses, museums, critics, theorists and artists say it is – art is beauty, and as such lies in the eyes of the beholder.

WRITTEN BY JEANIE LO

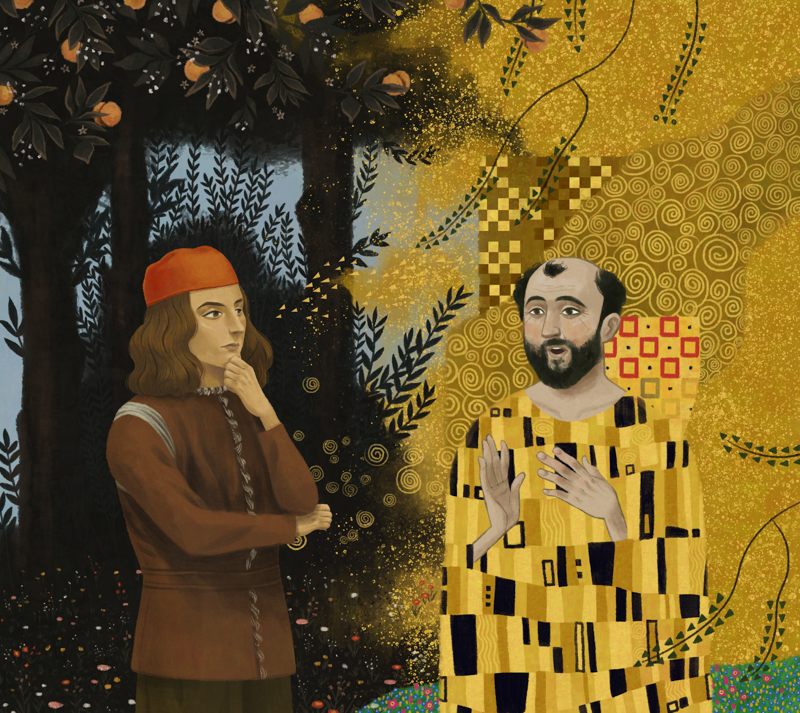

ILLUSTRATED BY ALEXANDRA BADIU

Rumor has it that Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci, giants of the Renaissance and some of the most iconic artists of all time, were actually bitter rivals. Not only did they compete for commissions, they mocked each other’s work and argued over the definition of true art.

Rumor has it that Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci, giants of the Renaissance and some of the most iconic artists of all time, were actually bitter rivals. Not only did they compete for commissions, they mocked each other’s work and argued over the definition of true art.

Da Vinci was an avid painter, and he considered painting as the supreme art. Supposedly, Da Vinci once told Michelangelo he was not a real artist because he could not paint. Rumor also has it that Michelangelo, who had always regarded himself as a sculptor first and painter second, accepted Pope Julius II’s commission to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel just to prove to Da Vinci he could excel in painting too. Michelangelo and Da Vinci’s feud shows us that even the most famous artists disagree with what could and should be considered art, a question that has persisted for centuries.

The definition of art changes according to time and social circumstances. Art historians during the Renaissance made the distinction between an artist versus a craftsman, while 18th-century theorists, critics and educators deemed photography as the lowest form of art, if it could be considered art at all. Duchamp’s 1917 “Fountain” mocked museums and provoked us to ask ourselves, “Is everything in a museum art? Even if it’s just a urinal?”

The general public find it difficult to agree on what can be considered art, especially when it comes to ready-made works, found objects and abstract paintings. Most visitors when they see Rothko’s color field paintings think, “My kid can do that,” or send a Snapchat of Robert Rauschenberg’s “White Painting” in the Museum of Modern Art with the caption, “WTF.”

So, what is art? As defined in the Oxford Dictionary, art is “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.” But this definition probably doesn’t satisfy those who think Rauschenberg’s painting is trash.

Another particularly polarizing piece is Tracey Emin’s “My Bed,” which was shortlisted for a prestigious Turner Prize in 1999. The work provoked a huge divide among both the art world and the public. “My Bed” is a king-size bed with white sheets, duvet cover and pillowcases covered in cigarettes butts, used condoms, menstrual blood and urine. Emin recalled she was always in her messy bed during a deep depression. Trapped by apathy and lethargy, she found hope one morning when she looked at her bed and thought “this bed had saved my life and kept me safe,” she said in an interview with Turner Contemporary. “At that moment I just saw it in a white space, and I realized it was art.”

The response, however, questioned that. News outlets published headlines titled, “Is this art?” in response to her work. Art historian and exhibition organizer Richard Dormant called Emin a phony. Many asked, “Where is the beauty associated with classical art? Where is the grace?” Emin didn’t even make the fabrics or materials. However, the interpretation of modern art judges more on intellectual content than criteria of beauty. Some critics saw “My Bed” as a confessional piece that brought forth a sense of intimacy and a visualization of depression and trauma. It revealed the human experience.

Gyun Hur, a faculty member at Parsons School of Design, said that Emin’s work “is art as a portion of the artist’s past life re-contextualized in the art space,” and that “her approach in this particular work references back to Duchamp’s ready-made works, in which there is no fabrication or ‘artist’s craftsmanship’ visible in the work, but just the conceptual way of thinking about objects, space and concept.”

Cheska Inciong, a second-year painting student at SCAD Hong Kong, said she thought it wasn’t up to her to define if Emin’s work is art. “Just the fact that she wanted to preserve a memory and document something important to her seems significant,” said Inciong.

When asked how she personally defines art, Inciong said, “Art is another form of communication between people. Whether an institution or auction house considers a work as art doesn’t really define it as art.” What she does consider art is something that connects with people, makes them feel less alone and allows them to see their own experiences and emotions mirrored in the works. Inciong references “Orphan Girl At the Cemetery” by Eugène Delacroix as art, not only because it’s skillfully painted, but meaningful. “It made me feel something,” Inciong said. “I look at it, and I feel a connection to someone else. I like it because it feels vulnerable.”

When asked how she personally defines art, Inciong said, “Art is another form of communication between people. Whether an institution or auction house considers a work as art doesn’t really define it as art.” What she does consider art is something that connects with people, makes them feel less alone and allows them to see their own experiences and emotions mirrored in the works. Inciong references “Orphan Girl At the Cemetery” by Eugène Delacroix as art, not only because it’s skillfully painted, but meaningful. “It made me feel something,” Inciong said. “I look at it, and I feel a connection to someone else. I like it because it feels vulnerable.”

Clay Randle, a second-year writing student at SCAD Atlanta, sees art as a product of self-actualization. “Art is the highest manifestation of one’s imagination,” Randle said. “What drives art is the ability to look at the world and, no matter the circumstance, still see purity. Art is about maintaining a natural point of view and an appreciation of the small things in life which are often overlooked.” Randle added that “all art is perspective-based and opinions will differ.”

For Yeliz Motro, a second-year animation student at SCAD Atlanta, effort and sincerity in art are what matter most. “If I see something that has a lot of effort put into it, I tend to appreciate it more,” she said. “After I recognize the effort, my next checkpoint is usually uniqueness and genuineness. For example, a low- budget movie that has a new thing to say, an unusual perspective or a different approach to filmmaking which has a lot of heart and soul will always be better for me than a high-budget, very well-produced one that follows a standardized method.”

“Before Sunrise” (1995) is one such film according to Motro. “You can see the effort that was put into making the characters feel real and their relationship even more real. The dialogue and the tiny gestures and expressions of the two characters make up the whole movie. The cinematography or lighting or anything isn’t over the top. All the effort was put into making the story feel genuine and intimate.”

Every student has their own definition, yet we can see a pattern: our definition of art is often an emotional one. Art itself already carries and conveys feelings — it’s a vehicle of expression that evokes our emotional responses as well. Think of the look of anguish on Michelangelo’s Mary in the “Pieta” that made visitors sobbed, the horror reflected on the face of the man in Munch’s “The Scream,” or the heart-warming scene in Pixar’s “Up” that chronicles Carl and Ellie’s relationship and had thousands of people commenting on its YouTube link how it made them cry. Our reactions to art are personal. And when it’s personal, the definition of art becomes subjective.

So, we must ask ourselves a question: just because we don’t like a work of art, does it mean it’s not art? In the debate over what defines art, I thought of what novelist Leo Tolstoy wrote in “Anna Karenina” that “there are as many minds as there are heads … there are as many kinds of love as there are hearts.” To me, it seems there are as many kinds of definitions of art as there are people, living and dead. According to the High Museum’s public relations specialist Noella Jones, the definition of art “is constantly evolving, thanks to innovative artists who push us to see the world differently.”

So, we must ask ourselves a question: just because we don’t like a work of art, does it mean it’s not art? In the debate over what defines art, I thought of what novelist Leo Tolstoy wrote in “Anna Karenina” that “there are as many minds as there are heads … there are as many kinds of love as there are hearts.” To me, it seems there are as many kinds of definitions of art as there are people, living and dead. According to the High Museum’s public relations specialist Noella Jones, the definition of art “is constantly evolving, thanks to innovative artists who push us to see the world differently.”

One thing that unites us all though, is no matter how our diverse and different our definition of art is, most of us have at least something to say about it: “This is art!” or, “No, this is not art!” We disagree over what art means, because it means something to us. Art meant the life to Michelangelo and Da Vinci, which is why each artist was so passionate about defending their chosen medium of art as the “true” art.

How we define art is a subjective opinion rather than an objective, unbiased truth, yet the experience of art is universal. It tells us something about our individual need to find things like meaning, genuine connection, preservation of memory, documentation and social change. Our personal definitions of art are a reflection of out principles and values. So, it’s okay to express your admiration or distaste for different types of art, and it’s okay to say whether you think a work is art or not. In the end, it’s a reflection of your values and it means something to you, no matter what that something might be.