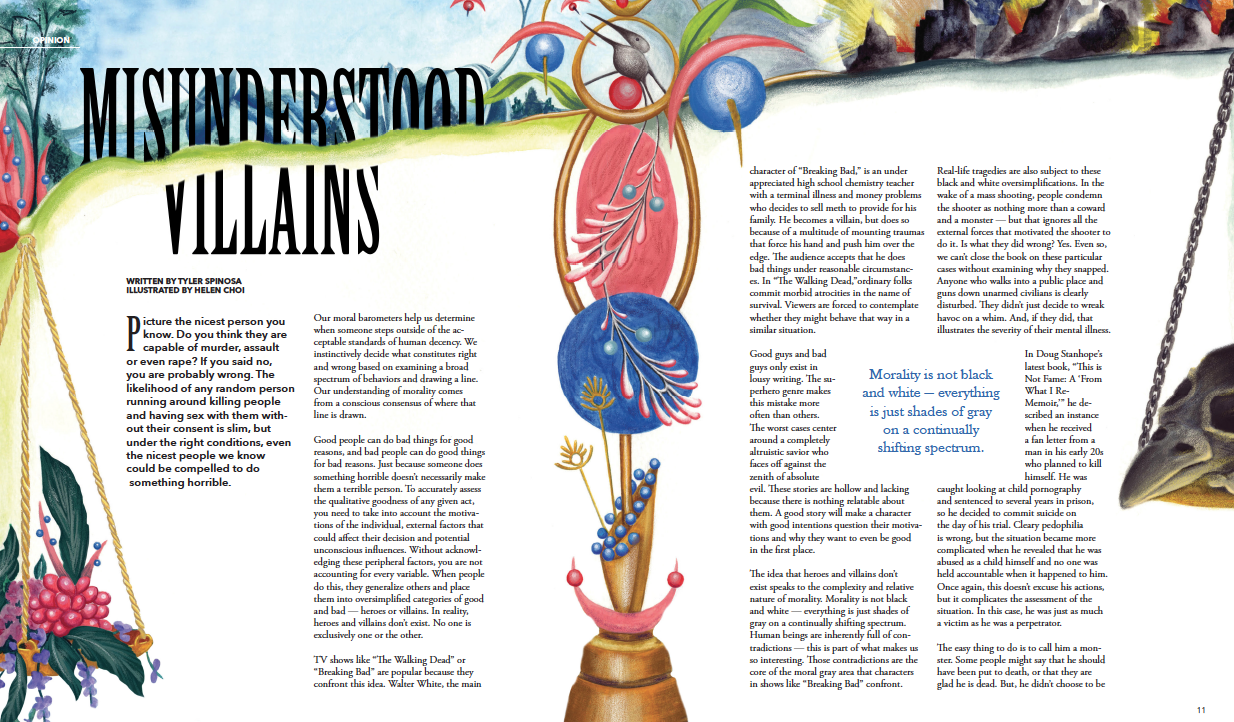

WRITTEN BY TYLER SPINOSA

ILLUSTRATED BY HELEN CHOI

Picture the nicest person you know. Do you think they are capable of murder, assault or even rape? If you said no, you are probably wrong. The likelihood of any random person running around killing people and having sex with them without their consent is slim, but under the right conditions, even the nicest people we know could be compelled to do something horrible.

Our moral barometers help us determine when someone steps outside of the acceptable standards of human decency. We instinctively decide what constitutes right and wrong based on examining a broad spectrum of behaviors and drawing a line. Our understanding of morality comes from a conscious consensus of where that line is drawn.

Goo d people can do bad things for good reasons, and bad people can do good things for bad reasons. Just because someone does something horrible doesn’t necessarily make them a terrible person. To accurately assess the qualitative goodness of any given act, you need to take into account the motivations of the individual, external factors that could affect their decision and potential unconscious influences. Without acknowledging these peripheral factors, you are not accounting for every variable. When people do this, they generalize others and place them into oversimplified categories of good and bad — heroes or villains. In reality, heroes and villains don’t exist. No one is exclusively one or the other.

d people can do bad things for good reasons, and bad people can do good things for bad reasons. Just because someone does something horrible doesn’t necessarily make them a terrible person. To accurately assess the qualitative goodness of any given act, you need to take into account the motivations of the individual, external factors that could affect their decision and potential unconscious influences. Without acknowledging these peripheral factors, you are not accounting for every variable. When people do this, they generalize others and place them into oversimplified categories of good and bad — heroes or villains. In reality, heroes and villains don’t exist. No one is exclusively one or the other.

TV shows like “The Walking Dead” or “Breaking Bad” are popular because they confront this idea. Walter White, the main character of “Breaking Bad,” is an underappreciated high school chemistry teacher with a terminal illness and money problems who decides to sell methamphetamines to provide for his family. He becomes a villain, but does so because of a multitude of mounting traumas that force his hand and push him over the edge. The audience accepts that he does bad things under reasonable circumstances. In “The Walking Dead,”ordinary folks commit morbid atrocities in the name of survival. Viewers are forced to contemplate whether they might behave that way in a similar situation.

Good guys and bad guys only exist in lousy writing. The superhero genre makes this mistake more often than others. The worst cases center around a completely altruistic savior who faces off against the zenith of absolute evil. These stories are hollow and lacking because there is nothing relatable about them. A good story will make a character with good intentions question their motivations and why they want to even be good in the first place.

The idea that heroes and villains don’t exist speaks to the complexity and relative nature of morality. Morality is not black and white — everything is just shades of gray on a continually shifting spectrum. Human beings are inherently full of contradictions — this is part of what makes us so interesting. Those contradictions are the core of the moral gray area that characters in shows like “Breaking Bad” confront.

Real life tragedies are also subject to these black-and-white oversimplifications. In the wake of a mass shooting, people condemn the shooter as nothing more than a coward and a monster — but that ignores all the external forces that motivated the shooter to do it. Is what they did wrong? Yes. Even so, we can’t close the book on these particular cases without examining why they snapped. Anyone who walks into a public place and guns down unarmed civilians is clearly disturbed. They didn’t just decide to wreak havoc on a whim. And, if they did, that illustrates the severity of their mental illnesses.

In Doug Stanhope’s latest book, “This is Not Fame: A ‘From What I Re-Memoir,’” he described an instance when he received a fan letter from a man in his early 20s who planned to kill himself. He was caught looking at child pornography and sentenced to several years in prison, so he decided to commit suicide on the day of his trial. Cleary pedophilia is wrong, but the situation became more complicated when he revealed that he was abused as a child himself and no one was held accountable when it happened to him. Once again, this doesn’t excuse his actions, but it complicates the assessment of the situation. In this case, he was just as much a victim as he was a perpetrator.

The easy thing to do is to call him a monster. Some people might say that he should have been put to death, or that they are glad he is dead. But, he didn’t choose to be that way any more than anyone else chooses their sexuality. With these things in mind, it becomes less clear where the moral line is. Can you write him off as evil, beyond redemption, and undeserving of empathy when he is really just mentally ill? To do so is to place yourself on a moral high ground.

The easy thing to do is to call him a monster. Some people might say that he should have been put to death, or that they are glad he is dead. But, he didn’t choose to be that way any more than anyone else chooses their sexuality. With these things in mind, it becomes less clear where the moral line is. Can you write him off as evil, beyond redemption, and undeserving of empathy when he is really just mentally ill? To do so is to place yourself on a moral high ground.

What we see during times of crisis is a compulsion to label those who have made mistakes and caused harm as evil instead of accepting that there are complicated reasons behind why people do what they do. Those reasons don’t excuse their actions, but they inform them in a way that is too important to dismiss. People are not only capable of doing good and bad things, but they can even do both at the same time.

What we see during times of crisis is a compulsion to label those who have made mistakes and caused harm as evil instead of accepting that there are complicated reasons behind why people do what they do. Those reasons don’t excuse their actions, but they inform them in a way that is too important to dismiss. People are not only capable of doing good and bad things, but they can even do both at the same time.

The larger issue is that people look at the worst examples of human behavior — murder, rape assault and abuse — and try to separate the perpetrators from themselves as if they are not capable of doing something similar, given the right circumstances. It is a reactionary defense mechanism that shelters them from having to confront the reality of their own capacity for malevolence.

The Milgram Experiment, a behavioral study of obedience conducted at Yale University in 1963, tested the notion that people can be influenced to commit atrocities. The test subject was placed in front of a switchboard with a range of buttons corresponding to a device that administered electric shocks. Overseen by an administrator, the test subject was instructed to ask the secondary subject, who was hooked up to the device, questions. Each time they get one wrong the test subject was told to shock them with greater intensity.

The Milgram Experiment, a behavioral study of obedience conducted at Yale University in 1963, tested the notion that people can be influenced to commit atrocities. The test subject was placed in front of a switchboard with a range of buttons corresponding to a device that administered electric shocks. Overseen by an administrator, the test subject was instructed to ask the secondary subject, who was hooked up to the device, questions. Each time they get one wrong the test subject was told to shock them with greater intensity.

The trick here is that the secondary subject wasn’t really being shocked. They were actors, instructed by the administrators to show increasing signs of distress as the experiment continued. Eventually, the actor would plead for their life and beg the test subject to stop administering shocks.

Most individuals tested continued to shock the actors, even after they begged them to stop. Any time someone showed hesitation or concern, the administrators assured them that everything was fine and urged them to continue. Even though the people involved could have chosen to leave at any time, they stayed because they were encouraged by the administrators. This proves that, despite the fact we assume we are above certain actions, we can be influenced into doing something terrible with enough encouragement.

People tend to consider themselves above it all. They reject the idea that they could ever stoop so low. This is self-aggrandizing and wrong. We are all fallible and capable of evil. Anyone who denies that is trying to hide from their own inner demons.

People tend to consider themselves above it all. They reject the idea that they could ever stoop so low. This is self-aggrandizing and wrong. We are all fallible and capable of evil. Anyone who denies that is trying to hide from their own inner demons.

Are you defined by the worst thing you have ever done? You might be inclined to give yourself the benefit of the doubt when it comes to that question, but not other people. Instead of condemning those who do bad deeds, we should recognize the relative nature of morality and how that reflects upon ourselves. Examine why people do what they do and accept that human beings are full of contradictions. Don’t oversimplify the world by reducing it to black-and-white categories. Confront the gray area of morality by acknowledging your own capacity for malevolence.