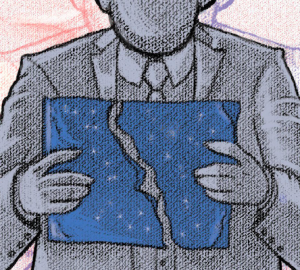

Torn Identity

A personal essay on growing up in-between cultures, searching for a sense of belonging.

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY MASHA ZHDANOVA

Something about valuing my heritage and culture feels backward and wrong, while at the same time, forgetting that heritage feels shameful and worse. I was born in Moscow, Russia. My family moved to the United States when I was 2 years old. I think in English, but at home, I speak Russian. The majority of my relatives still live in Russia. When I was a child, we would visit every summer vacation.

Something about valuing my heritage and culture feels backward and wrong, while at the same time, forgetting that heritage feels shameful and worse. I was born in Moscow, Russia. My family moved to the United States when I was 2 years old. I think in English, but at home, I speak Russian. The majority of my relatives still live in Russia. When I was a child, we would visit every summer vacation.

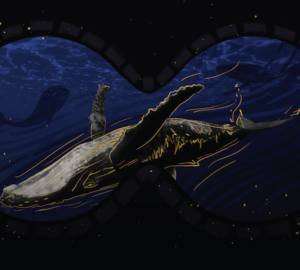

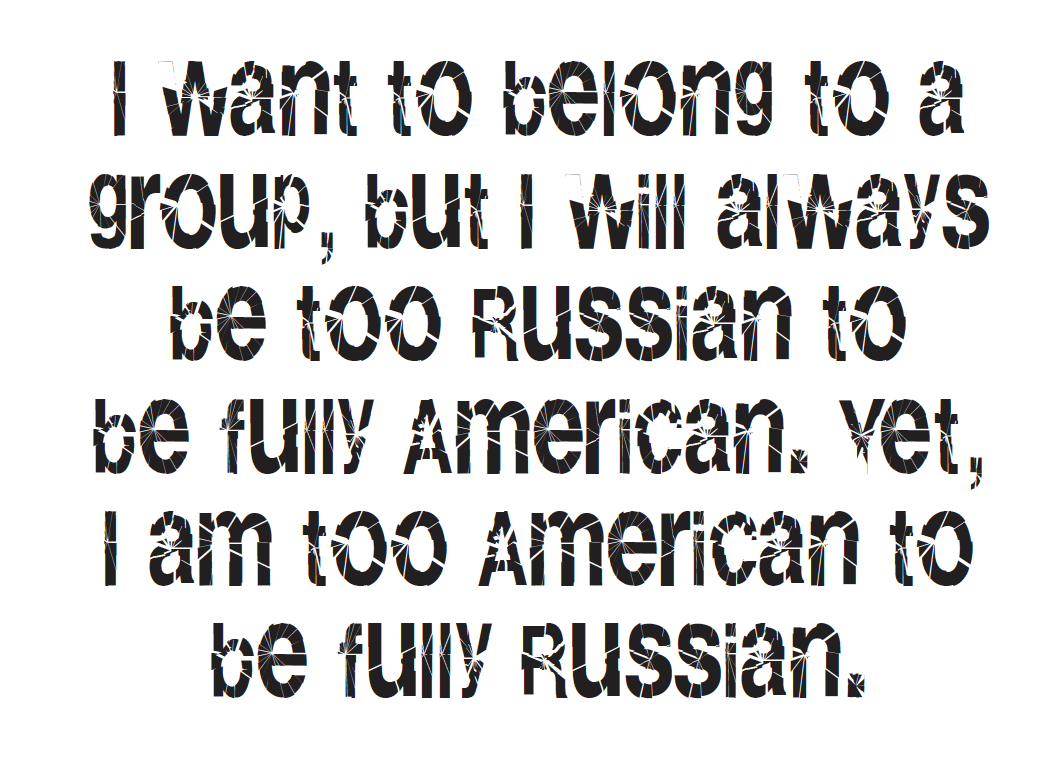

I’d always rather fit in than stand out. I want to belong to a group, but I will always be too Russian to be fully American. Yet, I am too American to be fully Russian. I want to be normal and feel part of a community, but as someone who grew up with influences and values from two very different cultures, I don’t really fit into either.

When I was a child, my mother would seriously talk about sending me back to Russia for a few years to go to school. “They’re stricter in Russia, you’ll learn better discipline,” she’d say, “and get better at math.” The knowledge that my place in this country is not and never will be permanently assured is terrifying. Particularly now, as new immigration laws could mean naturalized citizens like me are at risk of losing citizenship status.

My last trip to Russia was for two weeks when I was 16. The overwhelming feeling then was that I was too American to be able to live comfortably in Russia ever again. I’d lived in the same suburban New Jersey town since I was 6 years old. When I think of “home” now, I think of bubble tea, wandering deer and the bookstore my friends and I meet up at when we go to Princeton. The places I stayed at when I visited Russia felt like what “home” could have been, had my mom not decided to get her M.B.A. in the U.S., had she not decided to stay here afterward, had I gone back to Russia with my dad when they divorced.

I don’t always hate it. I’m fluent in two languages — enough to listen to music, read books and watch shows in Russian and English without subtitles. My Russian’s better than most kids raised in the U.S., so I can talk to my grandparents who don’t speak English without any problems. I don’t really get modern Russian slang, and my vocabulary is approximately equivalent to that of a 12-year-old, but I don’t have an accent and can quote enough classics that older Russians visiting the country will compliment my family on raising me well.

I don’t always hate it. I’m fluent in two languages — enough to listen to music, read books and watch shows in Russian and English without subtitles. My Russian’s better than most kids raised in the U.S., so I can talk to my grandparents who don’t speak English without any problems. I don’t really get modern Russian slang, and my vocabulary is approximately equivalent to that of a 12-year-old, but I don’t have an accent and can quote enough classics that older Russians visiting the country will compliment my family on raising me well.

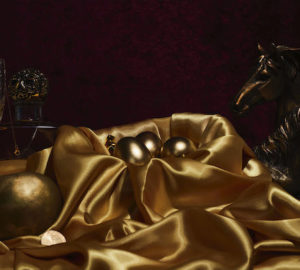

I do have positive memories of Russia from my childhood, before I was old enough to feel affected by politics — fresh fruits and vegetables from my grandmother’s garden, huge shiny churches and museums older than the U.S. itself, the beautiful, deep Moscow metro. I’ve also found common ground with immigrant children from other countries like China and India. Growing up, we’d bond over the work ethic our parents drilled into us, prioritizing education, weird food and even weirder family dynamics. I still remember an advanced math class in eighth grade when our whole class of 18 students, none of which had parents born in the U.S., discussed the different multiplication table charts our parents made us memorize in kindergarten. Mine had cute forest animals on it and said, “ТАБЛИЦА УМНОЖЕНИЯ” (multiplication table) in glossy red letters at the top.

“Did your mom make you do exercises from Russian math workbooks?” the boy sitting next to me asked. “Because mine made me do Chinese math workbooks.”

“God, yeah,” I replied with a laugh. “Maybe that’s why we’re all in this class now.”

When I was older, my mom invited me to come with her to a music festival. There were a few performers I liked, so I was interested. But, as I explained to my internet friends, it was a Russian-American music festival, and I was worried about it being “too Russian.”

“What do you mean by ‘too Russian’?” one of my friends asked.

“idk,” I typed. “I feel like if I go, it’ll signify that I’m not a fully assimilated American young adult. I also often worry that I’m forgetting my cultural heritage because my Russian isn’t quite as good as it would’ve been if I’d grown up in Russia.” I tacked on a “lmao” to lighten my words and hit send.

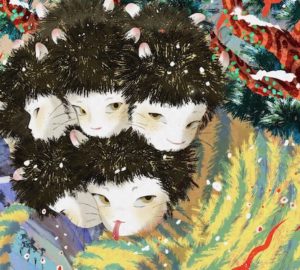

There weren’t a whole lot of Russian-American kids in my town — maybe five or six I’d spend time with. We’d speak English with each other, unless we wanted to quote something specific our parents said. We talked mostly about school and our interests and lives, and rarely about Russian things.

I visited one of those friends recently, bringing her a box of my favorite Russian desserts from the Net Cost Market in Philadelphia. Her family had, like mine, immigrated to the U.S. when she was 2 years old and went back every summer vacation. I played her some music by the ’90s Russian rock band Nol’, the frontman of which was the headliner at the festival I’d gone to the week before.

“This song’s really famous,” I told her when the intro to Lenin Street started. “So at the festival, he stopped singing on the last chorus and just had the audience sing it for him — it was awesome.”

“How I hate, how I love my motherland,” Fedor Chistyakov sang in Russian. “She’s blind and deaf and ugly, but there’s nothing else for me to love.”

“Do you get it?” I asked my friend, in English. “Yeah,” she said after a moment. “I do.”

I still feel not quite part of any country. I’ve joined some Facebook groups for Russian-American immigrants, but most of the people in those groups are closer to my mother’s age than my own, which is weird. I’ve found groups in which I feel like I belong based on my interests, but those friends don’t understand the cultural identity stuff. When I make comics or posts that draw on the immigrant experience — or the Russian-American experience — and put them online, I always get a few people commenting that it strikes a chord with them. That it means something to them, to see their specific and personal life experiences reflected by someone else’s work.

So maybe I’ll never really belong, but maybe that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Green isn’t just the average of blue and yellow, it’s a distinct color of its own. So, maybe the in-between space I occupy in society isn’t in between two countries or nationalities, but a distinct place in itself.