Expectations vs. Reality

Preparing for inevitable failure — and coming out stronger because of it.

WRITTEN BY JEANIE LO

ILLUSTRATED BY HENGGUANG LI

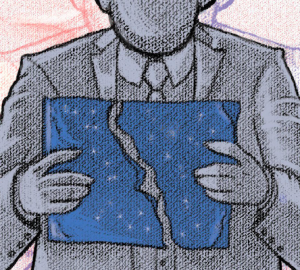

You enrolled at SCAD expecting a summer internship at Pixar or DreamWorks, not working as a barista at your local Starbucks. You think you’ll score a part-time job with your 4.0 GPA, but the company gave the position to your best friend. You produce your best work in class, but the teacher gives you a C when you expect an A. Welcome to reality, where dreams are dashed and hearts are broken. This is the reality — not our expectations.

There are several layers to expectations. We expect ourselves to be incredibly talented and highly qualified, but reality proved otherwise. We hope the world would reward us for our hard work, but it responded with rejections. We think the translation of expectations into reality will make us happy — except when they don’t.

Let’s unpack this starting from our expectations of ourselves. More often than not, our perceptions of ourselves don’t match up with who we are in reality. We believe we are gifted in unusual ways — that we are different, unique and special. We think we are excellent draftsmen and that our concepts are profound. Yet, although we might be talented, we just aren’t as great as we think.

In school, if our peers or professors don’t give us the appreciation we think we deserve, we turn sour, bitter and angry at the world. SCAD Savannah student counselor Cathy Traynor said, “Most of us, generally speaking, don’t want to perceive ourselves in a bad light.” Our instinctual response to criticism is usually defensive. We tend to vilify people when they cannot give us what we want. Traynor concluded, “It can take quite a lot for us to admit that we are less than perfect — or less than nice in certain situations.” Not only does our tight grip on our incomplete assessment of ourselves affect our mood and self-esteem, but it also hinders our career and creative process as we indulge in self-pity and pit ourselves against the world.

Introspection helps us dismantle this troubled mindset. Traynor explained, using the example of getting a bad grade — “Let’s say the students have a horrible color theory professor and they just couldn’t work it out. They don’t just think the professor is wrong. Instead, they think about if they did something that contributes to that. They think about ‘what I could have done better.'” Introspection is the ability to see how our negative emotions cloud our objective assessment of ourselves. It helps us effectively separate our feelings from judgment. As we accept our limitations and weaknesses, we can improve a situation by controlling our responsibilities, responses and actions.

Introspection helps us dismantle this troubled mindset. Traynor explained, using the example of getting a bad grade — “Let’s say the students have a horrible color theory professor and they just couldn’t work it out. They don’t just think the professor is wrong. Instead, they think about if they did something that contributes to that. They think about ‘what I could have done better.'” Introspection is the ability to see how our negative emotions cloud our objective assessment of ourselves. It helps us effectively separate our feelings from judgment. As we accept our limitations and weaknesses, we can improve a situation by controlling our responsibilities, responses and actions.

There are cruel realities we must also come to terms with when we realize our expectations will never come true — sometimes because we lack the ability. SCAD photography B.F.A. alumnus and freelance photographer Foon Fu’s dream in high school was to become a professional athlete. As he reached college, “it hit me, and I came to realize my expectation of becoming an elite, professional athlete was not going to happen. I had failed miserably,” he said. His experience led him to “realize how mortal I am, how it takes multiple pieces at the right place to make a masterpiece, and the life of a professional athlete was not going to be the puzzle I could make into a masterpiece.” The realization was hard to process, but the acceptance of a spoiled dream was how he learned how to keep moving on in life without giving up. It was his lesson of learning to accept “failure, rejection and not always getting everything you wanted.”

Entitlement is a cousin of expectation. In our culture, we are encouraged to think we are entitled to certain rewards once we have done the right things — that we can achieve whatever we believe we can do. Yet, it’s a hard fact that the world does not owe us anything. We can’t always get what we want.

Beyond the self is society. How about when we already have a realistic assessment of our abilities, we gave our best, we evaluate our performances and we adjust — yet our environment does not reward us with what we think we deserve. SCAD alumnus Mark Ziemer graduated college to his dream job as a graphic designer before becoming art director for Atlanta magazine’s Custom Media Division. For a couple of years, his career was on the rise and his goals were clear — until problems with resources surfaced and destabilized Ziemer’s life. “Even when you land that ‘dream’ job, life throws you curveballs,” Ziemer said, but he didn’t retreat into despair, “you have to adapt. It’s like if a project isn’t working out and your professor wants you to redo it a week before finals.” He endured seasons of challenges until he started working at the Atlanta Department of City Planning. “Don’t sulk. Hustle, learn new skills. Raw talent is great, but it’s only half the battle,” he advised, “and don’t be discouraged.”

Beyond the self is society. How about when we already have a realistic assessment of our abilities, we gave our best, we evaluate our performances and we adjust — yet our environment does not reward us with what we think we deserve. SCAD alumnus Mark Ziemer graduated college to his dream job as a graphic designer before becoming art director for Atlanta magazine’s Custom Media Division. For a couple of years, his career was on the rise and his goals were clear — until problems with resources surfaced and destabilized Ziemer’s life. “Even when you land that ‘dream’ job, life throws you curveballs,” Ziemer said, but he didn’t retreat into despair, “you have to adapt. It’s like if a project isn’t working out and your professor wants you to redo it a week before finals.” He endured seasons of challenges until he started working at the Atlanta Department of City Planning. “Don’t sulk. Hustle, learn new skills. Raw talent is great, but it’s only half the battle,” he advised, “and don’t be discouraged.”

It’s crucial to analyze circumstances objectively and acknowledge uncontrollable factors that lead to rejections. Like Ziemer, there are situations where we have all the credential a job requires, yet we still get rejected. SCAD Atlanta student success adviser Dinh Nguyen shared his observations about students’ unrealistic expectations. “A lot of students that come and see me expect to go directly into their dream job after graduation right away,” Nguyen said. He understood that as students paid a good amount of money to come to SCAD, “they expect with their perfect GPA they will have great offers and near six figures salary thrown at them.” The world doesn’t operate according to our logic — you don’t always get to reap what you sow. Nguyen said, “you could do all the right things, and the right opportunity might not come up for you.“

Jen Schwartz, former Editor-in-Chief of SCAN Magazine and current senior content writer at HeadsUp Marketing, expected to land a job with her leadership experience. When she adjusted her mindset and learned to accept opportunities that were not part of her goals, she started from the bottom and applied to an internship that led to her current job. Schwartz’s advice? “Apply to anything and everything, even if it’s not as glamorous or high-up as you would have imagined yourself being post-college.”

The reality is companies don’t only hire people based on merits. Employers also look at your personal qualities and whether your personality fits into their working culture. Even hobbies matter — chemist Jonathan Yip works in a marine biology lab and observed that all his colleagues have diving certifications. Many experience rejection after a great interview yet score the position after a horrible one. It’s hard to predict or control success.

Finally, here’s what I call the real reality — expectations that become true do not always make you the happiest.

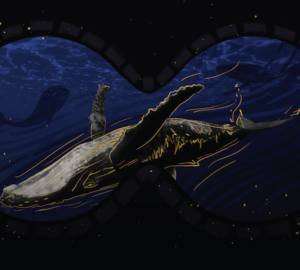

In his TED Talk, “Why we’re unhappy — the expectation gap,” founder and CEO of 180 Degrees Consulting and Rhodes scholar Nat Ware concluded that people are terrible at predicting what makes them happy. Just like how we can overestimate ourselves, we are prone to faulty judgments of thinking only by getting what we want will make us satisfied — the job, the salary, the person we want to meet. This faulty judgment applies not just to our careers but to all areas of our lives. It could be the person of our dreams we want to date, but we end up realizing they are not as wonderful as we fantasized. It could be that movie we were dying to watch, but discovered the experience was not as incredible as we thought it would be.

In his TED Talk, “Why we’re unhappy — the expectation gap,” founder and CEO of 180 Degrees Consulting and Rhodes scholar Nat Ware concluded that people are terrible at predicting what makes them happy. Just like how we can overestimate ourselves, we are prone to faulty judgments of thinking only by getting what we want will make us satisfied — the job, the salary, the person we want to meet. This faulty judgment applies not just to our careers but to all areas of our lives. It could be the person of our dreams we want to date, but we end up realizing they are not as wonderful as we fantasized. It could be that movie we were dying to watch, but discovered the experience was not as incredible as we thought it would be.

To close this expectation gap, we must be open to seeing each undesirable incident as an opportunity — not only for growth but also training lessons that prepare us for a set of destinations that suits us better in our journey. Many SCAD students took a detour before coming to art school, studying engineering or politics before realizing their potential is better suited toward the creative field. Those initial experiences that we had do not go to waste — they are additional facets we bring to the table. I studied art history at my first university before transferring to SCAD. Though I am a writing student, my background in art history helped me score my first internship at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. My writing skills aided my work in their social media and communications department.

Expectations are not bad — they are expressions of our desires and aspirations. Whether realistic or not, we should always respect our dreams because they represent a part of our personality and character. We need to be open-minded and flexible when our reality checks come in and adapt to circumstances when they require us to. What’s most important is that we understand a fulfilling life means overcoming rejections and struggles. Happiness is not a destination — it’s a byproduct of our journey. Lowering expectations is not the only way to happiness. Having an open mind and welcoming new possibilities will bring us the fulfillment and meaning we crave in our lives.

Expectations are not bad — they are expressions of our desires and aspirations. Whether realistic or not, we should always respect our dreams because they represent a part of our personality and character. We need to be open-minded and flexible when our reality checks come in and adapt to circumstances when they require us to. What’s most important is that we understand a fulfilling life means overcoming rejections and struggles. Happiness is not a destination — it’s a byproduct of our journey. Lowering expectations is not the only way to happiness. Having an open mind and welcoming new possibilities will bring us the fulfillment and meaning we crave in our lives.