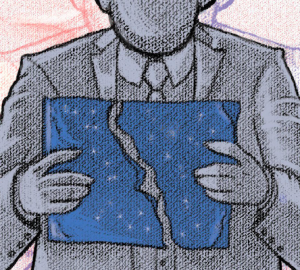

Dissecting the long-held idea expectation.

Written by Annika Harley

Illustration by Evian Le

Typography by Fon Limsomwong

Long before I asked her to sit for an interview, I watched my girlfriend Gabi lose her belief in the American dream in real time. We grew up in the same suburb outside of Washington, DC, and I watched as we ended up taking the leap out of the safety of our small town and settling down in Atlanta. We didn’t know we grew up in a bubble until we left it.

Our hometown was fairly homogeneous, the same polite white picket fences tucked into shady tree-lined neighborhoods on the banks of the Potomac. Everyone’s parents were doctors, lawyers, or government adjacent, and we all enjoyed the benefits of growing up in homes with a median household income of $128,000. We attended Fairfax County Public Schools, a school district with an A-plus rating and a coinciding budget of $3.4 billion for the 2022 school year. We were enrolled at a high school with a 99% graduation rate and where 82% of the student body participated in Advanced Placement classes. We were all expected to continue our education at a four-year college after matriculation. And how could we not, with our parents and peers making up the 31.8% of adults in Fairfax county with a postgraduate degree, compared to the national average of 12.8%?

For Gabi and I, this was all a given, we never knew life to be any other way. When we first learned of the American dream in elementary school, the idea that if a person works hard enough they can succeed beyond their wildest dreams, we believed it. Success was all around us, and we all made sure to put in the hard work so we could achieve even more than our parents had. We got private coaches so we could play varsity sports, we worked with SAT tutors to improve our scores, we hired private college advisors to help with the application process and get into a top university. We put in the work so that we could succeed, and, lo and behold, we did. So when we learned about people around the country unable to pick themselves up out of poverty with the virtue of hard work, it didn’t quite compute. We had bought into the idea that social mobility is achievable with a good attitude and a strong work ethic. When we put in the effort, we got what we wanted. Why didn’t that apply to everybody else?

It took volunteering at the local homeless shelter, Atlanta Mission, for both Gabi and me to see what life was like outside the sheltered campus and upbringing. The demographics at Atlanta Mission reflected those of the country at large, wherein “Among the nation’s racial and ethnic groups, Black Americans have the highest rate of homelessness.”

If you are a steadfast believer in the American dream, likely you buy into the idea that social mobility is available to those that just put in the effort. You might be inclined to think that the men and women I met at Atlanta Mission are just “lazy”, and that they never worked hard enough to get the life they wanted. I only had to visit once to learn just how wrong that is. They didn’t lose their housing because they were lazy. Almost every single one of the residents I talked to was working a back-breaking job, and often more than one, when they lost their housing. They lost it because their job didn’t pay them enough to cover their rent, because they couldn’t afford childcare and therefore couldn’t work, or because their medical bills bankrupted them and sent them into the street.

The country is inundated with people like the residents at the shelter who never had opportunities to begin with, and I think a huge factor in their circumstances is the lack of access to basic education. The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness found that “youth with less than a high school diploma or GED have a 346% higher risk of experiencing homelessness than youth with at least a high school degree.” Homelessness is practically inevitable when education is unavailable.

It’s gotten to the point that the American dream is drilled into children in public school to illustrate all the opportunities we can have if we work hard enough, however, we don’t learn the fact that those opportunities may be limited to a choice few of the population. Gabi and I were lucky enough to be a part of the privileged few. To be fair, Gabi doesn’t like the idea that everything was handed to us. She studied for 8 months for her SAT, took 12 AP classes, and graduated with a 4.9 GPA to get into Emory, a prestigious university with only a 13% acceptance rate. As a result, she’ll likely graduate to a starting salary of $60,919 a year at only 21 years old. That took hard work, hard work that she committed herself to since she was in seventh grade. But none of that would have been possible without the resources that are readily available for students like Gabi in places like Fairfax County. Families are capable of shelling out the big bucks for private tutors and private college admissions advisors alike. Resources are plentiful, and not just for those willing to pay a little extra. Publicly funded schools in the Fairfax public school system all have free tutoring provided by teachers and students alike during and after school hours.

Then why is a good education so hard to find in other cities? It took leaving Northern Virginia and some research for Gabi and me to figure out that not all school systems look like Fairfax. Gabi and I recently listened to an NPR feature story about the Normandy school district, a district so desperately under performing that it lost accreditation by the state of Missouri from 2013-2017. In light of the fact that 28% of its students would be transferring to accredited schools, Normandy’s 2013 budget was reduced to $50 million, only a fraction of the $2.4 billion 2013 Fairfax budget, for a student population that is 92.1% African American and 44% economically disadvantaged. Closer to home, Georgia’s Clayton County schools, just south of Atlanta, lost accreditation in 2008, losing all of its public funding, and leaving a population that is 62.9% African American, 22.7% Hispanic/Latino to fend for themselves. Even after regaining accreditation in 2013, Clayton County Public Schools proposed budget for the 2023 school year is only $945 million. All these numbers have me wondering; why are underfunded school systems primarily districts with large minority populations?

There’s a handful of answers to these questions, all pointing in the same direction. A study by the

US Census Bureau found that school funding comes in three parts: 45% local money, 45% from the state, and 10% federal. Most of the local money provided is sourced from property taxes, which vary from district to district. In poorer neighborhoods, the state can foot the bill, but that aid doesn’t even come close to matching the funding that high-income areas receive. Because residents of wealthy towns can also be hostile toward the construction of low-income housing in their neighborhoods, the gap between rich and poor districts becomes even more dramatic.

A report by Bellwether Education found that school districts with a distinct lack of affordable housing generate $4,664 more in per-pupil funding compared to the average district. Thus, Fairfax County, a district with a median value housing unit price of $576,700, gets $3.4 billion in public school funding, while Clayton County Public Schools, a district with a median value housing unit price of $122,100, gets only $945 million. With state-sanctioned district boundaries heavily influenced by a history of racial segregation and redlining, the underfunded districts almost always end up being the

districts with a large minority population. Bellwether refers to the practice of state officials and realtors lumping all the affordable housing into one district as “educational gerrymandering.”

Again, I ask, for whom is the American dream achievable? Is it accessible to students in unaccredited school districts with four-day school weeks, defunct classrooms, uncertified teachers, and parent volunteers in place of professionals in the classroom? Or is it only available to those whose parents both have master’s degrees and bring in $128,000 a year in annual income? Life beyond the homeless shelter can be unimaginable when a good education was never an option. When it comes to opportunity, it seems like many poor minorities never had a chance in the first place.