Written by Benjamin Greennagel

Illustrated by Keith Alexander Lee

When I was six years old, I received an invitation to a Halloween party. I was particularly allured by the fact that I was expected to wear a costume, and I spent every afternoon picking through my sister’s closet until I had crafted the perfect ensemble. When the day of the party finally arrived, I pushed through the white picket gate of my best friend’s backyard, my plastic tiara gleaming on top of my head and my long, sequined gown trailing on the grass behind me. It took me at least an hour before I even noticed that I was the only boy who came dressed as a princess.

From a young age, I have been drawn to stories about characters I can relate to, which were feminine people who felt out of control and those who struggled to belong. Reading these stories made me feel as though I was part of a coalition, standing alongside the princesses who, despite their circumstances, found empowerment through their personal relationships with the natural world. As I grew older, I realized that these princesses seem to stand side by side with each other, too, as their core values echo in folktales around the world.

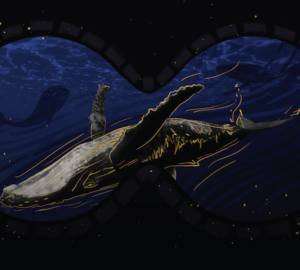

“Sleeping Beauty,” France

Many people believe Sleeping Beauty is one of the most passive heroines of the fairy tale genre. It’s not as simple as that; her tale contains complex ideas and disturbing content, and it is her reaction to these events that denotes her as an empowered person who has merely been impacted by things that are outside of her control.

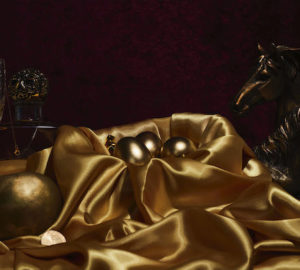

Most of the narrative details have remained consistent since early iterations of this story were published by Giambattista Basile, Charles Perrault and The Brothers Grimm. In the beginning, Sleeping Beauty is cursed by a wicked fairy, who is angry and vengeful after being denied an invitation to the princess’s christening. Later in life, when the princess pricks her finger on a spinning wheel, she falls into a deep slumber. Over the years, her palace is engulfed by briars and sharp thorns. A century later, a prince finds the castle buried deep in the woods, and he cuts through the foliage to find the sleeping princess.

This is where the original story deviates from modern retellings. The prince is taken with the princess’s beauty but dismayed by the fact she is sleeping. He rapes her, leaving her pregnant with twins. The children are eventually born while their mother sleeps, then they suckle the poisonous needle from her fingertips, waking her up.

The spinning wheel was a reference to the string spun by the Fates of Greek mythology, who determine the beginning, middle and end of each human’s life. This symbol was a way for French and German storytellers to explore the idea of immortality and controlling one’s fate. When the princess pricks her finger on the legendary object, she is granted a form of eternal life, sleeping soundly in the forest without aging for a century. But the course of her life is determined by those around her, usually in a violent manner, which demonstrates the objectifying and deeply harmful perception of women at that time. This is one thing that initially drew me to the story; Sleeping Beauty seeks peace and reunion with her family. She is protected by a council of women, who are the other twelve fairies of the forest, and she is ultimately saved by her own children, not by the man who violated her.

Disney recently explored another retelling of this story with the 2014 film “Maleficent,” which follows the wicked fairy, who, after being betrayed by a human man, developed a grudge for both the man and humankind. Although Maleficent is a reimagination of the 1959 adaptation of Sleeping Beauty, taking many liberties with the plot, it doesn’t stray far from the original themes of the story: vengeance, misogyny, greed and the loss of innocence.

“Yeh Shen,” China

The story of Yeh Shen is one of the oldest variants of “Cinderella,” predating Perrault’s famous retelling by several centuries. This version was first published during the Tang dynasty by Duan Chengshi, around 850 C.E. Once again, the tale is remarkably consistent throughout the years, featuring an evil stepmother, a lazy stepsister and a lost slipper, though this one was made of silk, not glass or gold. Many readers are critical of Yeh Shen and her variants, believing that they were at the mercy of their male love interests. But almost every version of the story shows our protagonist cultivating a firm sense of hope and an optimistic perspective of her future before falling in love, despite being raised in an abusive environment. I am particularly inspired by this tale, as it is ultimately about perseverance and faith.

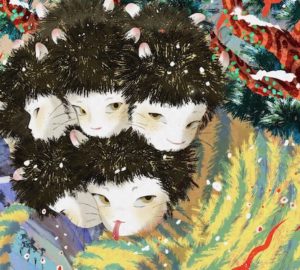

At the beginning of the story, Yeh Shen establishes her relationship with the natural world by befriending a goldfish in her backyard pond. The fish becomes her confidant, and they spend every moment of Yeh Shen’s free time speaking with each other. Unfortunately, the wicked stepmother discovers the goldfish and, out of spite, cooks it for dinner. That night, a mysterious street vendor meets Yeh Shen and instructs her to place the fish’s bones in four pots at the corners of her bed. Once she does this, she is able to speak to the fish, who has gained the ability to grant any wish. At Yeh Shen’s request, it provides her with a beautiful jade gown and silk slippers to wear to the ball. Ultimately, the emperor meets her and falls in love.

There are a few examples of how this story handles death. The goldfish attains a form of immortality and agency, affecting the plot even after its death. In one version of the ending, the stepmother and stepsister are buried in a tomb and later become goddesses who can grant wishes — an unusual but not unwelcome redemption arc for Yeh Shen’s family.

The goldfish is a common symbol in Chinese folklore, and we see it referenced again in Grace Lin’s novel “Where the Mountain Meets the Moon,” which was inspired by a slew of Chinese folktales. At the very beginning, the heroine, Minli, receives a magical talking goldfish from a mysterious street vendor. The fish becomes a guardian for Minli’s family and guides them home after the tumultuous events of the book. This might have been a reference to Yeh Shen’s best friend and the protective role it played in her life. This adaptation, as well as Yeh Shen and its different versions, often circles back to the same simple, evergreen advice: “Have courage and be kind.” (Cinderella, 2015).

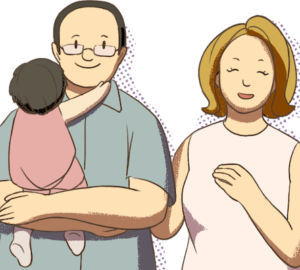

“The Bamboo Cutter and the Moon-Child,” Japan

This is one of the best-known folktales in Japan. It serves as a whimsical bedtime story and contains the classic components of a fairy tale, but it is also an etiological tale for one of the most notable geographic features of Japan.

One day, a bamboo cutter was wandering the forest at the base of Mount Fuji. He struck down a stalk of bamboo and found a tiny baby girl inside. She was radiant, like moonlight. The bamboo cutter took her home and raised her as his daughter. She grew up and began helping her father in the forest. Every time she joined him at work, he discovered gold inside the bamboo, and soon their fortune grew. Eventually, the emperor hears about the young woman and asks her to marry him. But then she reveals that she is a princess from the moon, where her kingdom has been seized by civil war. She was sent to earth for her safety, but she has decided to go home. To express her gratitude, she gives the emperor a note and a vial containing a potion that would grant him immortality. The emperor sets fire to the princess’s gift and leaves it at the top of Mount Fuji. The flame sinks into the heart of the mountain and never dies, which explains every volcanic eruption that has occurred at the site since then.

This tale also deals with the concept of death and defying fate in a more literal sense; it features the Elixir of Life, which first appeared in stories in this region thousands of years before it appeared in Europe. As a result, the Japanese word for immortality, 不死 (fushi), might have inspired the name of Mount Fuji, according to Live Japan Travel Guide. There is a refreshing twist in this story, as an immortal woman determines the emperor’s fate, rather than the opposite.

In 2013, an animated adaptation of the story was released. It was called “The Tale of Princess Kaguya,” after the moon princess in the original story. The film was produced by Studio Ghibli and was a departure from the style of animation audiences usually associate with the studio. The static landscape and flat, watercolor backgrounds meld harmoniously and many stills from the film emulate the pages of an old storybook — perhaps an homage to the ancient nature of Princess Kaguya’s story and the timeless role it has played in Japanese culture. This adaptation looks at the behavior of humans from a critical perspective, as Kaguya prays to the moon and deals with her disenchanted expectations of living as a mortal on Earth. Although she does appreciate aspects of her human life, she ultimately decides that her strongest empowerment came from her relationship with the Buddha and the life she led on the moon.

Before ancient storytellers brought folktales over mountain ranges and riverbeds, feeding them into the mythology of new cultures, they each told the same story, with explanations for the inexplicable and quests that felt both heroic and mundane. Each princess is bound by fate and social expectations, yet the actions that drive their stories are most often driven by the values obtained in spite of their circumstances. Echoed throughout their stories is one overwhelming human desire that transcended borders and wove its way into the folk tales around the world: a desire to triumph over evil. To live free of pain. Perhaps it is the simplicity and totality of this notion that make stories about princesses so appealing to children. Whether we wear plastic tiaras or silk slippers, we adorn them as symbols of autonomy and hope.