By: Jackson Williams

If Dad hollered my name, I answered — especially during my evening rounds on the farm. I usually photographed the animals after my chores, but developing the photos would have to wait. I sprinted from the sheep pen to the back porch of my house, and by the time I arrived, Dad scrambled for his hat and coat — things he only wore during winter, church or a trip into town. It was a clear Monday in August, so I knew something was wrong when he grabbed my shoulder with his calloused, firm hand.

“You’re in charge,” he told me without elaboration.

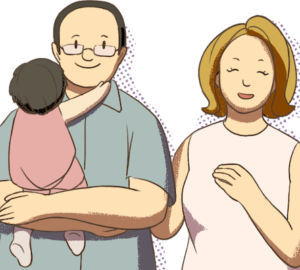

Those words were sharp in my mind as I sat on Mama’s bed, placing a damp washcloth on her forehead, trying to reduce her fever. She said Dad went to fetch her some medicine the doctor recommended for her nasty illness. She patted my back in slow, controlled rhythms with her frail hand. Even in sickness, Mama cared for others.

“Don’t you fret over me, Davis. Once I get that medicine, I’ll be good,” she said and forced a chapped-lip smile before taking a sip of water. “You mind closing the window when you leave? Those windchimes keep rattling, but the wind isn’t reaching me.”

“Sure thing,” I said and nodded to her heavily pregnant stomach. “But it’s not only you that I’m anxious about.”

Mama rested her head on the pillow and took a deep breath. The mattress creaked as I slid off Mama’s soft bed. Soon, the scent of baby powder and laundered blankets would replace the lavender perfume and pine that clung to the sheets. Even sooner, my animal photographs on the wall would be replaced with newborn pictures. I shut her window and cut the lights, leaving only the glowing firefly mobile over the baby’s crib.

Our dog, Red, barked a loud whimper from downstairs and his heavy paws smacked the back screen door. Mama winced at the noise and pressed a hand to her head.

“I’ll go see what he wants. Get some rest, alright?”

She waved me off and pulled the blanket to her chest, after which I rushed out the door with my dog. Red dashed ahead of me, crossing the length of our farm with ease. My chest tightened as we passed the cows who quietly slept in their pasture and the chickens safe in their coop because only one enclosure sat to the North: the sheep.

I could’ve sworn that I secured the pen before Dad called me home, but the gate was wide open. Did I leave it unlocked? Dad was going to kill me if any sheep escaped. Red ducked and sniffed around the pen, wagging his fluffy tail and flaring his nostrils. I secured the enclosure — for sure, this time — and counted the sheep.

Fourteen … Fifteen … Sixteen. There were supposed to be seventeen sheep. I counted again — sixteen. I broke the numbers into ewes and lambs, and one ewe moved around more than the others, wagging her head in confusion. I shined my lantern on her underside and knew she was a mother sheep. I thought of how sad my mama would feel in that situation.

Red ran a few leaps into the woods and barked. It must be where the lamb went. My heart pumped against my chest, but I couldn’t be scared.

“Dad left me in charge.”

Before my trek into the woods, I left Red with the other sheep to make sure I’d hear the commotion if anything else went wrong tonight. The musky farm smell shrunk with every stride. It was pitch-black, save for the fireflies blinking across the trail. Cicadas whirred in the distance, where they’d abandon their husks in the morning for me to sweep them off the chicken coop. One tree supported an orange birdhouse with stripped paint from the many seasons it endured. Dead leaves crunched under my feet and the dewdrops reflected my dim lantern. The condensation sank through my sneakers. My next step nearly hit the dirt, paused for small hoof tracks dotted ahead. It had to be close.

The ground rumbled. It thundered with a weighted footstep and freezed any other movement. It got closer, shifting somewhere behind me. Heavier than a lamb, heavier than a feral hog too. A twig snap made me whip around, but only fireflies danced in hypnotizing waves in the now-silent atmosphere. I followed them deeper into the mass of trees. Mama always told me that these bugs protect the forest, and I could stay out until they went to sleep. She was real strict about being home before that. She was superstitious, all right. Did they even sleep at night?

A scream punctured the air like a bullet, and it wasn’t human. The familiar cry of a lamb echoed in panicked desperation until it strained like a hand grabbing a record — warped, struggling, piercing. It stopped as quickly as it started. Interrupted.

I should look for it. I should see if the little lamb was only frightened and tripped over. My body refused, washing an anxious wave of lead over any righteous actions my brain wished to take. Smart cowards lived longer than brave idiots, right? I walked toward the noise. After all, the fireflies were up with me.

The trees parted to a grassy clearing of dandelions — no lamb in sight. Everything was still under the enormous harvest moon, which was unusual for this time of year. I didn’t even remember seeing it. Cicadas quit whirring, and the grass was dry while my feet remained wet from the nervous sweat accumulated over my skin. I smelled something metallic, similar to ozone or gasoline. It stung my nose. And while I was sure the lamb’s cry came from this direction, nothing was here except a ringing like my house’s windchimes. I had to be a mile or two from home by now. I’d never been to this part of the forest because the fireflies stopped flitting around here. Did they go to sleep?

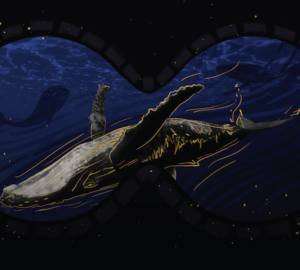

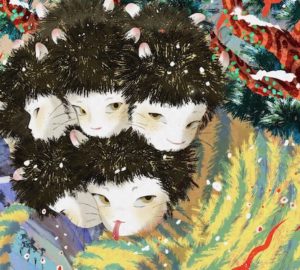

The ground rumbled again, and the metallic clinking crescendoed until a tall, lanky creature stalked into the clearing. As the black mass approached in jerky, patient movements, my throat tightened with nausea. It was taller than any bear but as thin as a human, crawling with rickety limbs. Rattling jars of fireflies hung from its waist, illuminating skin as pale and flaky as lichen. Its skull wore thinly-stretched human skin that bore no eyes, nose, or lips. Every sensory area was hollow except for more fireflies floating like pupils in the eye sockets. The mouth was the worst of all — a snake-like, unhinged jaw with another jar shoved inside, preventing it from closing. The object pushed the head to uncomfortably tilt back, causing the creature’s body to bend forward like a bird. Drool slid down the glass jar and dripped to the ground like a leaky pipe.

It took every ounce of willpower to step backward. And I’d been hunting with Dad enough times to recognize this scene. Like a chess piece, I inched away again. One of us had to make a move, and my small frame was incredibly outmatched in this unfamiliar part of the woods. Now, the creature stopped. Now, I ran.

I might as well have been running on air with how light the dirt felt beneath me, especially with the titan chasing from behind. Every tree and landmark blurred past and sunk into the nightmarish landscape. My lungs and calves burned from the adrenaline as if saying, “you’re not dying here!” Again, my mind disagreed. I was being hunted by something beyond anything natural. And I’d only seen helicopters from a distance, but I could imagine the experience up-close for the first time.

A cool wind whisked my skin from behind despite my hot body temperature. I checked over my shoulder, where I saw the creature’s entirety in front of the harvest moon, unmasked from its cloak. Insect wings spanned from its back, allowing two insect arms and feet to dangle while two human arms reached out like a crucifix. The jars bumped and rang while it followed me through the lightless labyrinth of the backcountry.

My hunter crossed more ground than I could outrun and the buzzing closed in. Distracted, a root snagged my foot and slammed my right side into the dusty foliage, causing my head to pound from the impact. People felt bruises before they see them, and it felt like my brain got replaced with sloshing water. Stunned from the wipeout, I couldn’t move as the creature landed in front of me. Staring at its grotesque face and crooked, gumless teeth took my mind from the forming concussion. Its sharp hand extended, shiny with half-dried blood and white fur — a result of the lost lamb. Something poked into my leg, and it hurt when I tried to drag myself away.

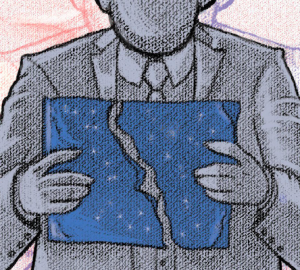

I slowly rolled onto my back and reached into my pocket, where my camera lens was cracked. With a shaky hand, I raised it to the light catcher that stared into my soul with its cavernous eyes. I clicked the flash to capture the monstrosity. While it pondered my offering, time went from immediate to infinite.

“I can catch light too.”

Its large hand clawed my camera with a surgeon’s precision, close enough contact for me. The machine shuttered in rapid fury, erupting bright bursts between us. Small photo cards printed and fell like an autumn leaves. When the camera couldn’t print any more, the light catcher pushed it into its ribcage by ripping into its leathery skin, joining it to the most horrifying ecosystem I’d ever witnessed.

The light catcher receded into the shroud of endless trees — a glowing silhouette interrupting the dark as I stood to my feet and I pondered how long it lived in the woods behind my home, chiming on windless nights.