A Photo Series and Personal Essay about growing up in Appalachia

Written by Megan Elizabeth Smith

Photography by Ellie Briggs

I never knew how lucky I was until three summers ago. While everyone was locked away from the world, I found myself on top of a mountain, looking out across the valley below. My home away from home.

I’m not sure why my great-grandfather decided to come out to Maggie Valley in the first place. As the story goes, he repurposed wood from an abandoned cabin he discovered out in Cherokee, brought the pieces back to Maggie, and built his cabin on a 20-acre plot of land. Thank God he did. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be standing here today. My dad always spoke of him in such high regard. He spent every summer out here working alongside my great-grandad, building porches and reaping the fruits of his labor. That time spent in the Great Smokey Mountains must’ve impacted him quite a bit, so much that in September 2019, he and my mom decided to pick up their lives and move out there.

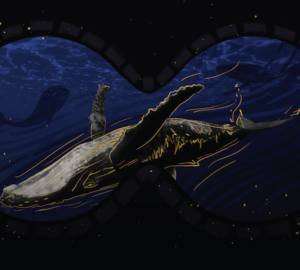

What perfect timing. See, out in Maggie, COVID-19 didn’t hit much, nor did the rest of the world’s problems. It felt like a whole different universe inside this snow globe scenery where the chaos of the living seemed to cease. It was simple. People ‘round there do about the same damn thing every damn day, and when they ask you how you’re doing, they mean it. Everyone walks at a slower pace, not just because they’re old, but because the world doesn’t need to move a million miles a minute here.

If you’re moving that fast, how will you ever take the time to smell the pine trees? It’s those little moments of quiet that mean the most, yet in the outside world, we seem to be completely devoid of them. I know I was.

Being immersed in the world of Appalachia was the trigger. Tradition is held in such high regard because, beyond the walls of the valley, it doesn’t seem to exist much. The folks here might not know about BeReal or James Charles’ latest cancellation, but they can tell you all about the history of the Appalachian mountain dulcimer. They probably even own one, and I’ll bet its origins are not that of a factory but from ole’ John up the road, who said he’d carve one out for ya if you’ll help him load up some lumber for the barn he’s building. The practices I see people engage in might seem ancient to the outside world, but here, it’s a way of life. Despite being a seamstress most of my life, I’ve seen more women here who practice needlecraft than ever before. That effect carries over. I watched my own mother pick up a cross stitch project she had started back in 1990 and finally finish it. It only took her 30 years, but that time is woven into each individual thread as a testament to her persistence. I even found myself picking up the crochet needle again and practicing what my grandmother had taught me when I was ten, but I had since put down. All these pieces of myself and my family that had been lost to the modern world seemed to reawaken. Not only did we come back to these practices—we came back to ourselves. We came back home.

When I moved out there, I didn’t realize the impact it would have on me. In all honesty, it didn’t fully hit me until two years later when I flew across the pond to study abroad in Lacoste and found myself, once again, on top of a mountain, in very different circumstances. I would’ve wasted my time sitting on my phone (not like I had service anyway). I quickly realized that I was spending my days doing the same things the folks back in Maggie do: sitting on their porches, needlecraft in hand, and looking out on the prettiest view you’ve ever did seen. All at once, these experiences and processes I had observed for so long seemed to culminate. Suddenly, everything made sense. Even if it took me traveling halfway across the world to realize how special my home is, so be it. It’s in the quiet moments where we find ourselves, and finally, without distraction, I found so much more.