Written by Alejandro Bastidas

Illustrated by Rachel Ong

This is the story of a dead writer. Nameless, sunken under Time’s cruel currents as it happens to those who dare leave their mark in literature and fail, for a great number of reasons, but in the end become victims of their own creative devices. Was the writer’s quill cursed? (Actually, he was so poor he couldn’t afford ink. The man used a makeshift pencil of mysterious origin instead). Was his imagination not really his own but rather the product of arcane forces? All we can do is speculate. Surprisingly, this writer had friends. Among them was the great Mary Shelley, who, unlike this other dead writer, cemented herself as one of the most influential authors of the century.

The hero in question needs a name. How about Alexander? Or Reginald? What about your name, dear reader? After all, you could find yourself in a similar position, forgotten and unremarkable after the arts drained the life out of you, so why not start practicing from now? Let’s call him Luke. The problem of the man’s story is the same as this one, or at least the portion you’ve read of this one, where a lot has been said but not much has happened. This sentiment could also describe the man’s life up to the point where his friend Lord Byron invited him to spend the spring in Geneva, along with Percy Shelley, Claire Clermont and Mary Godwin, who would later marry Percy and assume his last name. The trip to Geneva inspired Mary’s story well enough but also erased poor Luke from existence, after the writers locked him away in the back of their memories — and also a basement.

Geneva, 1816

Spring dressed up the willows in lush green braids but offered little else to the humble bushes and wildflowers frozen by the winter. The season’s turn led to an uncertain divorce between subzero evenings and scorching mornings, so Lord Byron did not know what to pack for the improvised trip to Geneva; he took all the coats with him and fled London without looking back. His name had been dragged in a scandal involving love affairs with foreign duchesses, a brawl with a British officer and the attempt to steal a Pre-Raphaelite painting. To lower suspicions regarding his abrupt disappearance, he invited friends over to the mansion, far away from gossip and the burden of high society.

When Lord Byron opened the door of his mansion and found Luke standing there in his tattered robes, bent-double and carrying a rucksack that looked stolen, he smiled — not out of genuine delight to reunite with an old friend, but out of egoism, realizing that Luke was by no means better off than him. Sure, Luke wasn’t a wanted man in his hometown, but he looked invisible, like the kind of person you’d turn away from if you ran into them on the street, the kind of person you’d gladly forget about, or choose to remember whenever you needed to boost your self-esteem.

“There he is!” said Lord Byron. “The man, the myth, the legend.”

Luke bowed his head in doubtful reverence and patted Byron’s shoulder. He was neither a hugger nor a talker. Luke wondered what it would take for a man to be considered a myth and a legend. Saving, killing or creating?

After supper, Lord Byron had planned a late-night trip to the mountains by the mansion. But the sightseeing was to be delayed to another day when a storm rattled Geneva, sending forks of lightning that frightened the host.

“I know!” called Lord Byron as the awkward silence of boredom invaded his guests. “We will each write a ghost story. Whoever writes the most frightening, visceral, sinister tale will win our undying respect and be forever welcome in my home.”

The guests agreed, some with more excitement than others, like Mary Godwin, whose quill was already in her hand at the time. Each guest found a quiet room to write in except for Luke, the man with the pencil, who had to carry a desk down to the basement before he could get to work.

“All respectable families follow tradition,” began Luke’s story, written upon the scraps of paper Mary Godwin had lent him. “Some are families of lawyers, and no other career choices are considered for the sons; some are families of bakers; some families manufacture political snobs for generations; other families, no less respectable but perhaps less fortunate, produce murderers. It is their inherited trait. Not just the capacity to take a human life, but the pleasure that comes with it …”

There he stopped to drink from Lord Byron’s wine and stepped away from his desk to think. What seemed like a promising beginning came to a sudden halt, the muse slipped back to the invisible world and never came back to him. Luke downed his cup. The last time he’d written anything was six years ago. Somebody told him he had a long career ahead of him, until Luke published his novel and was butchered by the critics, ridiculed in all of Scotland as a pathetic excuse of a writer and exiled himself to England where nobody knew his work.

As it happens, Luke tried to write the bones of his story in Lord Byron’s basement but realized there was no meat, nothing genuine to be savored, much less to frighten readers. He knew lawyers well enough: they’d sued him multiple times and drained his savings in the process. He also knew bakers, as he’d fallen in love with a baker’s daughter and tried to court her once, until a terrible sickness made her eyes bleed and she died in the bakery because no one cared enough to rush the baker’s daughter to the apothecary. But of murderers he knew the same as everyone, and that is, nothing true. It would take another sixty years for Jack the Ripper to arrive and start the obscure fascination with serial killers that seems so popular these days.

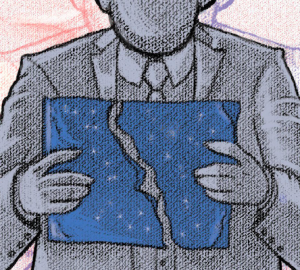

“This isn’t any good,” Luke said after three hours of writing, scrapping entire pieces of paper, pulling at his hair and recalling every insult thrown at him by the critics, to the point where his own handwriting withered into childish scribbles.

The door to the basement creaked open and snapped him out of his self-deprecating trance. It was Rita, the maid, coming down the stairs with a meal. Through the open door he heard Mary’s calm voice sharing a passage of her story, then a round of thunderous applause and praise from Percy Shelley, who encouraged her to keep writing. His curiosity made him stand from his desk and walk up the stairs. In the same instant, Rita tripped over her own feet and almost tumbled down the stairs, had Luke not been there to catch her in his arms.

The tray flew over their heads and almost crashed into the manuscript. Rita’s eyes were shut, her body tense as if anticipating the fall.

And there, holding her close to him, Luke realized her life was literally in his hands. She seemed smaller somehow. His grip tightened on her arms. Her eyes opened in surprise. He shoved her down the stairs.

Her frail body rolled to the depths of the basement, her whimpers filled the room. Luke’s shadow blocked the frail light from the open door above. He picked up a fallen knife and pounced on Rita as he imagined the characters in his story had done, that family of professional murderers, whose line of work he couldn’t quite describe, until that moment, when he stabbed the maid to death and rushed back to work with her blood still soaking his shirt and face. Crimson droplets stained the manuscript as his rushed handwriting filled the rest of the page with a detailed account of what he had done, what he had felt, a vile rush, an unstoppable hunger, a beast rising from the depths of himself — no, not himself. From his character’s self. Luke himself had killed no one. No one.

Upstairs, a nonchalant voice called to Rita over and over again, until the silence in response gave way to frustration and Lord Byron raised his tone as he did whenever somebody ignored him. Luke ignored the commotion and crafted another sentence detailing the texture of another person’s blood. A second voice called Rita. It was Mary’s, who claimed to have heard loud stomping down in the basement, finding it unusual for Rita to take so long in the simple task of leaving a meal for a guest.

“Luke!” she called. “Everything alright?”

The rushed scribbles stopped. Luke couldn’t keep writing with all those distractions. Never mind the pool of Rita’s blood under his feet. That he could tolerate. But not Mary’s incessant calling. He ought to silence her too, like he’d silenced Rita, with the same knife so he could give the object greater weight in the story. He left the pencil on his desk, picked up his weapon, then raced up the stairs, hopping over entire steps with inhuman speed. Mary peered down from the threshold and screamed at the sight of the haggard man covered in blood, a silver knife in his hand, eyes like the hollow sockets of a skeleton. She slammed the door shut before Luke could reach her. He barreled into the door. On the other side, Lord Byron screamed a series of commands. Percy Shelley and Claire Clermont dragged a heavy bookshelf to barricade the door and fixed a wooden stool under the door handle.

“Let me out,” Luke hissed. “I did what you asked. I wrote the story.”

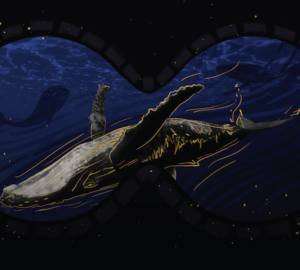

But nobody answered him. Nobody opened the door or asked him why he’d killed Rita. The other writers gathered in the living room to decide what to do with Luke, until they reached a unanimous agreement to leave the barricade where it stood, to leave the madman in the depths of the basement with the fresh corpse and his manuscript, where he could hurt no one who tried to confront him. It would take weeks for the constables to arrive and bring him to justice anyway. They found it best not to confront him. Not to remember him. They would leave the mansion the following day after reinforcing the barricade and never speak of the man again. They would keep on writing about other monsters, not knowing Luke would do the exact same thing in the basement and bury himself deeper into the story that became his life and his death, for he never finished the tale, starving in the darkness, talking to himself and Rita’s ghost.

Lord Byron’s mansion in Geneva still stands today, a macabre tourist attraction where literary enthusiasts go to conjure the image of Shelley writing the first draft of “Frankenstein,” not knowing it was there where she first witnessed a man, an inventor of sorts, driven mad by his creative obsessions. The man in question was forgotten. Down in the basement there are two dusty skeletons and a brittle, bloodstained manuscript. A pencil adorns the crooked desk like an afterthought. Some tourists swear they’ve heard incessant scribbles somewhere in the mansion, others suggest the stairs speak in a secret language of their own and unseen objects fall behind the door, always around the spring.