Written by Hannah Mosley

Illustrated by Ajani Pratt

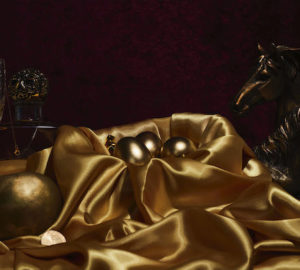

Luce listened, her whole body tense for the right moment. Slim, the gray cat curled in her lap, found her impatience irritating. He flicked one ear back and stretched, pricking her thigh with his claws through the patchwork quilt. She scratched between his ears and he turned to look at her, eyes glowing in the moonlight of the open window. It was a full, golden, end-of-summer moon. The buck moon. She had work to do.

The cat seemed to understand. He lifted his chin, sniffed the warm night air and sprang from the bed to the window ledge and down out of sight. Luce went through the checklist in her head. She had everything packed in the Food City bag already: kitchen shears, twine, a flashlight, an old jam jar, an empty water bottle, her favorite rocks, a candle, rosemary from her garden and a matchbook marked “Lucky’s.”

Down the hall, a screen door moaned then banged shut. Skeeee — BAM-bam-bam. Luce counted to five. Right on time, the truck engine sputtered to life.

It scattered gravel across Luce’s garden as it pulled out, its headlights swinging past her window and disappearing down the road. She was free. Daddy wouldn’t be back from Lucky’s until near dawn — more than enough time to get what she needed. She was already in running shorts and her mother’s old “Welcome to Fabulous LAS VEGAS Nevada” T-shirt from before Luce was born, when she and Daddy had lived there.

She threw back the quilt and grabbed her sneakers. The other children at school said “tennis shoes,” but she thought “sneakers” was more accurate. Her shoes weren’t for playing tennis. Granny had taught her that words — and especially names — held meaning.

Granny was her mother’s mother and what many of the older neighbors called a “granny woman”: a healer, a midwife. She took care of the neighbors before there was a doctor in town. When a real doctor moved in, he told people that Granny’s plants weren’t medicine. Granny could make a tincture to help you fight off a cold, but the doctor could give you something to kill it outright. And if the doctor invoked science, the neighbors got to thinking, what was it that Granny, whose mother had been Cherokee, called to her aid? It wasn’t anything Christian, to be sure. So neighbors stopped visiting her mountain. Their children began calling her a witch. Daddy told Luce she couldn’t see Granny anymore. Not that she had listened.

Luce tightened her laces, grabbed her supply bag and swung one leg and then the other out the window, dropping behind the azalea bush with practiced ease. Standing, she was barely taller than the azalea, which was getting leggy and overgrown in the heat. She’d cut her black hair short for the summer. Her skin was a deep tan from two months spent outside. Confederate jasmine and honeysuckle climbed the back wall of the tin-roofed shack and filled the evening with redolent perfume. She grabbed a yellow honeysuckle blossom, pinched the green calyx surrounding the bud and pulled the style slowly through the flower until a bead of nectar formed at the end. It tasted like summer.

Luce caught up with Slim, who was chasing fireflies in the long grass behind the house. They had just reached the trailhead when a light from a nearby copse of black gum trees caught her in the chest.

“Jeez, Lucinda, you look like you saw a ghost,” said a voice behind the flashlight.

“Who’s it?” Luce held her own light out like a sword in front of her and switched it on.

A boy stepped into her light. “Only me,” he said.

Henry Rayburn lived on the leeward side of the mountain, down by the fishing creek. When they were younger, Henry and Luce would spend their summers swimming in the creek and racing Henry’s hunting dogs down the dirt road that connected their houses. A few years ago, though, Henry had started playing football for the school team. He came over less often and then, not at all. When they started high school, he stopped talking to her all together. He was tall, blond and good-looking, and she was odd and boyish and the granddaughter of a medicine woman. There was an understanding that they moved in different social circles. Still, it was just Henry.

“That’s not my name,” she said and kept walking, which he took as an invitation to follow her. Slim hissed and shot off the path. “What are you doing here?” Luce said over her shoulder.

“I should ask you the same thing,” said Henry. He crashed through the woods behind her, breaking branches, stomping undergrowth. “You’re out here alone, at night, on a full moon, with a black cat. And you wonder why they call you a witch?”

“Slim is gray, not black.” She turned around. “Why are you here?”

“To see if you’re a witch.” He grinned.

“Well, I am. Now, go away. You’re making enough racket to spook the whole mountain.”

“Come on, Luce. Lighten up. If you send me away, I’ll be obligated to go tell your daddy what you’re doing. For your own safety, you know.”

His smile was a threat. A good one. If Daddy found out about where she was going, he’d board up her window and bolt her door. She’d have chores for the rest of the summer. It was bad enough last winter, when he caught the flu, and she’d put elderflower, echinacea and marigold in his tea. He’d made her do pushups on the gravel driveway and tore up her garden, saying afterwards it was to protect her, so that people wouldn’t drive her out of town like they had her mother. Which was ironic, since Mom hadn’t been driven out so much as she had run, and she hadn’t run so much from the town as from him, his temper and his drinking. Most of the time, he wasn’t too bad. Not really a dad, just someone she fed and cleaned up after. But recently, after long nights at the bar, he’d gotten into the habit of coming into her room, sitting on her bed and calling her Laura, her mother’s name. When he got like that, Luce was scared.

“Fine,” she said. “Swear you won’t snitch, or I’ll hex you.”

Henry held up the Scout sign. “Swear.”

She had hoped Henry would get tired of the hike and go home, but no such luck. They reached a cliff face of lichen-covered limestone. “Watch where I step,” Luce called. “It can get slippery.” She scrambled up and stepped into a clearing in the tree cover. The moon glowed gold above and lit up the surface of a small spring. All around its banks grew wild herbs. Luce pinched off yarrow and skullcap leaves and the tiny yellow flowers of St. John’s wort. The stinging nettles were next. She was used to their bite at this point, almost fond of it. Last, she needed valerian root. Henry pulled himself over the edge of the cliff, panting.

“You’re here to pick flowers?” he said.

“Not exciting enough for you?” Luce asked, uncovering the thin, pale roots. She snipped off the stems and bundled the roots in twine.

“You’re plenty exciting.” He picked a cluster of milkweed blooms and tucked it behind her ear. “But you’re not a witch.” She pulled out the water bottle and filled it from the spring. It was clear and bracingly cold.

“Here,” he said, pulling a metal flask out of his back pocket. “If you want a drink, have some of this.” He took a long swig.

“I don’t get it,” said Luce. “I thought you didn’t like me anymore.”

“It’s not that,” he said, running a hand through his hair. “You’re unapproachable at school, you’ve got your guard so far up.”

“I have to, around your friends.”

“They’re not that bad,” he said, trying to play it off with a smile. Luce turned away and started up the trail across the meadow.

“They are to me.”

Henry took her by the wrist. “Come on, Luce, have a drink with me. Let’s get trashed and go swimming in the creek. The moon’s out and we can swing over the blue hole like when we were kids —”

“You go,” she said, pulling her arm away. “I’ll catch up with you. There’s something else I have to do.”

She saw something shift in his eyes. A flash of anger, maybe? If he could tell she was lying, he didn’t say anything. “Okay, see ya later,” he said, and then he turned and began working back down the mountain, still draining the flask.

As soon as he dropped down the cliff, Slim reappeared ahead of Luce on the path. “Back on track,” she told him. It wasn’t far now, maybe a quarter mile up to Granny’s old house. No one went there anymore besides the occasional group of kids daring each other to go in “the witch’s house.” She was lucky tonight; she and Slim were alone. Around the back of the house, under an old, gnarled apple tree, was a small headstone. Atop the grave grew a fairy ring of mushrooms.

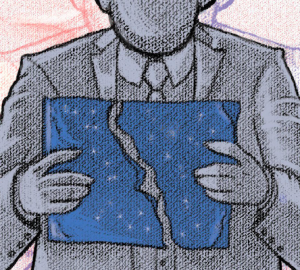

Luce hadn’t tried real magic before — she just knew what the herbs that grew around the mountain were naturally good for. Granny had taught her that most of an herb woman’s work was mundane: identification and recipe-making, trial and error. But every now and then, Granny would coax something extra from her blends. Luce needed that power now, needed a protection spell. She kneeled in the dirt and dumped out the Food City bag around her. Slim shot up the apple tree and turned his glowing eyes on something at the side of the house. A rat, most likely.

Inside the fairy ring, she arranged her favorite stones and stuck the candle in the center. Out came the herbs: nettle, yarrow and rosemary to protect her room. St. John’s wort, skullcap and valerian root to give her father restful sleep. She charred the root until it smoked and then cut everything with the kitchen shears. She sprinkled the mix with water from the spring and some of Granny’s grave dirt for power. She filled the jam jar halfway with salt and mixed everything together with the shears.

“Granny, I need your help on this one,” she whispered. “I need it to be strong. I need you to keep me safe.”

A voice behind her said, “You really are a witch.” It happened too fast. Henry pushed her to the ground, one hand on her back, and began fumbling for the waistband of her shorts. He was too heavy to throw off, but the shears, still in her hand, coated with herbs and salt, found their way into his side. He bellowed and reared back, and Luce scrambled up, backing away from the bleeding boy.

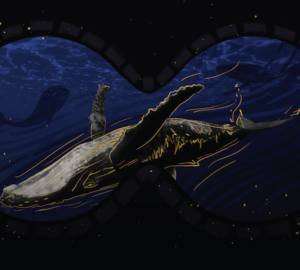

“I didn’t believe them,” Henry panted, “but they were right!” He stepped toward her, one hand holding his wound, the other picking up her candle. “You know what we do with witches? We burn ‘em!” He came at her with the candle. She grabbed the water bottle and, just as he stepped onto Granny’s grave, flung a stream of water at him.

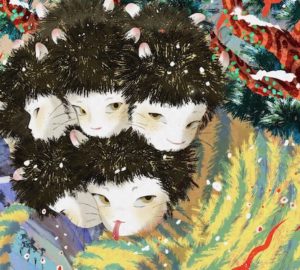

Henry gasped, and then his skin began to melt where the moonlight touched it. Luce screamed and backed into the tree behind her. His clothes and skin blurred and grew soft brown fur, his legs lost their bulk and became slender. He fell on all fours, landing not on his hands but cloven hooves. A short tail sprouted from his spine. His neck and face elongated, his eyes went black and wide, and cream-colored horns sprouted from his head.

Henry was gone. In his place stood a handsome young buck with six-point antlers and a wound in its paunch. The deer started and leaped past her and across the meadow, heading pell-mell down towards the Rayburn house.

Luce sat with her back against the apple tree and cried. Was she crying for Henry, the little boy who used to race her to the creek? Was it for what she had done to him — had she done that? Was it for what he had wanted to do to her? She kept telling herself she was safe until the shaking stopped.

Later, Luce collected her supplies and her cat and began the hike home. By the time she made it to the field behind her house, it was near dawn. The round, fat moon was still visible, but the sky was pale blue at the tips of the mountains and the valley was blanketed in low, damp clouds. Through the mist, she could see the headlights of a lone truck coming up the dirt road. Luce ran the rest of the way back to the house, hauled herself gracelessly through the window of her bedroom, grabbed the spell jar from the Food City bag and kicked the rest of it under her bed, and, as the truck pulled into the gravel drive, made a line of protection salt across the threshold of her room.

Skeeee — BAM-bam-bam. He was singing a tuneless rendition of a Hank Williams, Jr. song, “There’s a Tear in my Beer.” Luce kicked her sneakers off and slid under the covers. If he did come in, maybe he was too far gone to notice the evidence that she’d been out. “And then maybe my heart … won’t hurt me soooo,” he crooned, pausing outside her door. Luce heard him let out a tremendous sigh. He began to hum, and the tune carried him down the hall to his room and to sleep.

When she woke, Luce saw there were mud stains and blood splatters all over her mom’s Las Vegas shirt. She changed and took it to the kitchen sink to scrub. While it soaked, she put the coffee on and put four frozen waffles in the toaster.

“Mornin’, Lucy.”

“Hey, Daddy. Sleep good?”

“Like a log. I’m hungrier than a bear. Those all better be for me,” he said, gesturing to the toaster.

Luce nodded and poured them both some coffee. She wrung out the shirt and took it outside to dry.

“We were happy there,” he said, noticing the shirt. “I miss her too, you know?”

“I know you do,” said Luce.